At Roger Corman’s Concorde-New Horizons Studios in 1997, I opened a script file using Final Draft for the first time. It was on a “Macintosh” because I didn’t call them “Macs” back then. In short, with all due praise to John Hodgman, I was a “PC.”

- Movie Magic Screenwriter Crack

- Movie Magic Screenwriter 6.0

- Movie Magic Screenwriter 6.0 Serial Key Free

Story writer download - Movie Magic Screenwriter 6.0.5.89 download free - A very intuitive text editing software - free. software downloads - best software, shareware, demo and trialware.

A different kind of “PC,” Production Coordinator Joey Geiger laughed at me because I didn’t instinctively know to hit TAB to get from the scene heading to start typing the action text below. I hit RETURN, just like I’d done a billion times before when writing in Microsoft Word and other word processors.

Since then, I’ve written, co-written, or worked on hundreds of feature screenplays. But I’ve only used a small handful of screenwriting programs.

Why is that? Because there have only been a small handful of screenwriting programs available. And the two most dominant in the last decade or so? Movie Magic Screenwiter and Final Draft.

But as I write this article, I find it a bit odd that while marketplace is fairly replete with a score of alternatives as of the last half decade or so — FadeIn, Slugline, WriterDuet, Adobe Story, CeltX, Highland, Scrivener, etc. — the substance of many conversations and arguments about which screenwriting platform is the best (whether that conversation is in forums, or on Reddit, or in snarky blog comments) seems to always come back to someone asking the same question:

Should I use Movie Magic Screenwriter or Final Draft?

If the question is one I find repetitive — especially in a world where so many great new screenwriting apps are available, and at so much lower a price than “The Big Two” — then I can’t help but think that whenever developers of above mentioned newer screenwriting apps hear that question, they must experience some sort of collective, froth-at-the-mouth-style explosive diarrhea. Perhaps yes, or perhaps my imagination needs a repair.

Even I, posting a blog that pits “The Big Two,” against each other like I’m doing — or even referring to them as “The Big Two” — in a not-so-subtle way, reinforces the concept that these two software suites are the end-all-be-all of the screenwriting app world.

But what I’ve never seen, in all my internet travels hither and yon, is a detailed assessment of these two software suites, pitted against each other, using criteria and metrics that go beyond the “feature-bloat” features that each seem to suffer from, and go straight to the heart of what matters most:

How usable are these two programs to screenwriters in a real-world situation? (Whether that real world situation is multi-million-dollar film production or Jerry from Iowa and Jill from Washington writing the spec scripts that are going to save Hollywood.)

The fact is, most screenwriters aren’t the ones inside the Hollywood gates. Most screenwriters are the ones on the other side, with the pitchforks. (And now you know why they call them “pitches.”)

So how do these two screenwriting programs measure up? Both to one another and to the state of modern app usability, and to what screenwriters want and need from a screenwriting app?

That’s what I’m going to find out in this article, one feature or design flaw at a time.

How many people are using it?

Fact: Nobody wants to be the only gal in the room using the software that nobody else is using. It’s human nature to want to know, before you buy: What’s the best product?

Unfortunately, the best product isn’t always the one that’s most popular. Remember Betamax?

Kent Tessman, creator of the screenwriting app Fade In Pro says it plain: “Screenwriters should be able to use the best screenwriting software available without being encumbered primarily by what other people are using. “

And I agree. But when it comes to popularity, and number of users, Final Draft, at least for now and the immediate future, is the platform most screenwriters appear to be using.

However, let me drop in three personal observations when it comes to software popularity.

1) Consumers are increasingly less rigid about adopting new software as general computer literacy becomes more and more the de facto standard than an elite skillset our nation’s nephews and nieces used to browbeat their family members with whenever anyone couldn’t figure out how to, say, install an antivirus app.

2) Software is being developed in a much more agile way, and with far less overhead. As a result, software “suites” — software crammed with all sorts of bells and whistles — seem to be giving way to more nimble, better-designed apps which may contain only a fraction of the features of the “suites,” but allow what features that remain to be honed, perhaps to greater purpose and efficacy, if not a more graceful, less bloated user experience.

3) In the world of production and development, being on the same platform is not only helpful; it’s essential. A team of six writers working on such-and-such show for HBO can’t be using six different versions of the same screenwriting app, let alone six different versions of screenwriting app altogether.

But in the rest of the screenwriting world, where spec scripts — pro and amateur — continue to flood the festival, contest, and indie film space at a rate that outpaces the melt of the polar ice shelf (But, Uh, I’m Not A Scientist™), the only format that matters — the only format that you can bet they can open once it arrives in their email, or their Dropbox, or as a writer’s group forum attachment — is the almighty PDF.

And all screenwriting software platforms can create PDF’s.

So for the bulk of the screenwriting industry — the part that, ironically, may not be, literally, in the industry, per se (yet) — fretting about platform is an established screenwriter’s game; something to do while sipping Hennessy and smoking Cubans, sequestered in one of Hollywood’s many oak-paneled writers rooms, where people throw darts and eat pizza until 2AM and stay forever young and get paid by the wheelbarrow.

But let’s go with the premise, for this article at least, that platform choice — which software you choose to write scripts with — will continue to be relevant, and say that Final Draft and Screenwriter are the two biggest gorillas in the room.

Fluidity / Ease of Physical Typing

Both programs utilize the TAB-centric keystroke convention to get from one element to another. Screenwriter doesn’t assume that word one of your blank script is going to be a scene header/slugline until you start typing INT or EXT, whereas in Final Draft 9, you’re on a scene heading no matter what for the very first thing you type in your new script, unless you use a shortcut key from the manual or go to the top menu and change the element type to something else.

Neither program, to my knowledge, allows for quick, one-keystroke toggle of one line of text from one element to another. For example, sometimes I’ll start typing what I think is a line of action text, but realize the element type is set to a scene heading, (all caps). Or when editing, I’ll delete a few lines of dialogue or action and, in both programs, I’ll find that what was set as dialogue is now action, or something similarly wonky.

Windows server 2008 r2 standard x64 bit. Home » Guide » Evaluation Product Keys for Windows Server 2008 R2 Evaluation Product Keys for Windows Server 2008 R2 by A.J. Armstrong Published 10th October 2014 Updated 11th August 2018.

To fix that, instead of a simple keystroke toggle, I need to use the mouse for both programs, which has always been a downer for me. Keeping my fingers on the keyboard as much as possible is always optimal. Changing the element from scene heading to action requires selecting the text, dragging the cursor up to the top menu bar, and clicking through a series of menu items. Not a huge deal, but a real hindrance in both apps when trying to stay fluid while editing.

Design and Screen Real Estate

Something that’s always bugged me about both programs is how, well, ugly they are, and how much screen “real estate” they take up. While both have ample scene and note navigation sub-windows you can move around and size to your liking, the overall feeling I get from both programs is one of inelegance. They’re just too “cludgy.” Too many icons, too many boxes, too many windows, too many buttons to push in general.

An example of what I mean by cludgy is Final Draft’s Full Screen feature. It works, yes. But take a look at what I see on my 2560×1600 desktop when I have the Zoom set to 100% and I select “Enter Full Screen” in Final Draft:

As you can see, Final Draft is using the full screen to display the script I’m working on, technically I supposed, by simply hiding all the toolbars and windows, but my script is tiny. I know that’s technically my fault, as I’ve got the Zoom set to 100%, and that when I bump the Zoom up to the maximum 300%, I get something more like this:

… Which is more of what I’m looking for when I ask my app to take me to “Full Screen.” But therein lies the cludgy. When I go full screen, I want the entire screen to be filled with my script. I want the app to know that that’s what I’m after.

To Final Draft’s credit, Screenwriter doesn’t do it much better. They allow you to choose between “Normal,” and “Full Page,” but have no real “Full Screen” functionality. The best they offer is the ability to manually drag the font size of your script up (see image below), which allows you to manually fill the screen with your script via slider.

Again, not too elegant, but perhaps a step more towards control over the interface when it comes to full screen.

What’s missing from both: One click/one keystroke full-screen / distraction-free writing space that instinctively knows what size to set your text at, based on screen resolution.

Spellcheck

Both programs do a decent job of spellcheck, if you’re just looking to find misspelled words. What both programs fail at is finding mis-used words.

When I’m doing a proofread for a script sent into my company, Screenplay Readers, I’m not just doing a spellcheck, I’m doing a line-by-line manual check for misused words that neither Screenwriter nor Final Draft ever catch. You’re vs. your, they’re vs. their vs. their, loosing vs. losing — these are all extremely common errors, and it’s a flat-out shame that the built-in spellcheck of the two most popular screenwriting platforms can’t seem to catch them.

But if I have to choose the lesser of two weevils when it comes to spellcheck, I have to hand it by an inch to Screenwriter, which allows importation of “LXA” files (like anyone is gonna do that, but it might be great for non-English users) and more granular control over words in your custom dictionary than Final Draft. Final Draft lets your dictionary learn a word, but you can’t directly edit that word later; you can only delete it.

What would be great is if both platforms where somehow able to implement a technology like Ginger (an online dictionary / spellcheck service) or something similar, where the dictionary file wasn’t limited to the built-in list of words that shipped with the software, but instead was connected to a constantly-updated database. The online app Hemingway seems to be doing a good job of helping writers pare down their speech to the essentials, so I know this sort of technology is available, and suspect quite strongly that the developers of engines such as Ginger and Hemingway would be keen to expand their services to the Final Draft and Screenwriter user bases.

Updates and Support

Movie Magic Screenwriter Crack

When it comes to updating their software, between these two software suites, Final Draft wins, hands down. Movie Magic Screenwriter, as of press time, hasn’t seen an update since at least October of 2009. Final Draft seems to release a small fix or update every month or so. To be clear, the updates Final Draft has been releasing have been relatively minor, having to do with minor bugs or improvements. Still, that’s better than no updates since 2009, as appears to be the case with Screenwriter.

And when it comes to support, I can attest personally that both companies are manning the store and are attentive to their customers. Case in point for Final Draft: I wrote an article a while back about some alternative software that gave Final Draft a run for its money and Final Draft’s Product Manager Joe Jarvis emailed me directly within a day and offered a friendly response, as well as a spot on their Beta testing team for Final Draft 9.

When I first purchased Screenwriter over a decade ago, it was still named Movie Magic Screenwriter 2000. A decade later, and an upgrade to Screenwriter 6, and over a dozen installs and reinstalls later, my login and password and registration code still work just fine. Whenever I need to take Screenwriter off of one computer and put it on another, the automated process works like a charm. In the one instance I hit a hitch, a human in the office at Screenwriter headquarters had me on the phone and solved my problem.

Production Workflow

When it comes to breaking down a script, I myself rely fully on Screenwriter, due to the fact that it has always directly interfaced with Movie Magic / EP Scheduling and Budgeting. Final Draft hasn’t had the direct ability to do so up until recently. FD’s support site says that MM Scheduling will simply open a Final Draft 9 file, without having to import it. And it works, but at least in the version of Movie Magic Scheduling I’m using (6.01.400), it requires you to have a template file already open in Scheduling, and then actually does require you to use the Import function.

How the platform performs when it comes to production workflow isn’t likely to be a dealbreaker for the vast majority of screenwriters, who will not be using the app for actual live production. Those who do will find either workflow suitable.

How It Works With Other File Formats

It’s safe to assume that Screenwriter and Final Draft were designed with two things in mind: screenwriting and market share. Neither company should be faulted for putting out a product that utilizes an exclusive, proprietary file format, and neither company should be faulted for disallowing the use of their file formats in their counterpart’s software. (Imagine the headaches of trying to troubleshoot another company’s code when your own customers can’t open that company’s files on your platform!)

That being said, like the famous 60’s folk singer Ethel Merman once said, the times they are a’changin’. As I’ve expressed earlier in this article, the currency of the realm isn’t Final Draft, as much as they and a score of other bloggers would like you to believe — the currency of the realm is the PDF. And when it comes to what files open what software, the worm is clearly turning, ever-so-slowly, away from the binary formats of either of these companies and towards the text-based, XML-based screenplay file format.

Both programs export PDFs superbly. Neither program imports them.

As far as other imports / exports, Screenwriter is great when it comes to importing and exporting to and from production file formats, such as Movie Magic Scheduling, Gorilla, etc. But when it comes to import, it’s woefully underpowered. The only formats it can play with are Rich Text Format, Dramatica, and previous versions of Screenwriter.

Final Draft isn’t much better. Although it can import Highland files if those files are exported from Highland as Final Draft files, the app doesn’t allow for native import of Fountain-based text. To be clear, it DOES allow you to import those files if they’re saved as simple text files first. For that reason, when it comes to import/export, Final Draft beats out Screenwriter by a hair.

Nitpicks

If my previous complaints and observations weren’t “Andy Rooney” enough for you, let me dig into some minutia:

First of all, I feel it’s worth mentioning that for some inexplicable reason, Final Draft 9 doesn’t retain a list of recently opened files for me. Yet Screenwriter does it just fine. Could it be my install? I’ve only checked it on two installs: my desktop and my laptop.

Equally inexplicably, jumping to the beginning or end of a document in Final Draft using the HOME and END keys doesn’t work natively. If you prefer that feature, as I do, you’ll need to pop into the Final Draft preferences and deselect Scroll Keys Mimic MS Word.

And in the supremely-Andy-Rooney department, I have to confess, I can’t help but cringe at the look and feel and user experience of both companies’ websites.

Movie Magic Screenwriter 6.0

Yes, I went there.

Final Draft’s cluttery, slide-show, overly-e-commerced pages, jam-packed with stock imagery and too many links more often than not completely befuddles me as to what I’m supposed to click on next;

Screenwriter’s Web 1.0 site, with its too-small, mixed-up fonts and color palette straight out of my aunt’s quilt collection is only missing an odometer-esque visitor counter at the bottom and a warning that reads “This site is best viewed in 640×480 on Netscape 2.0” to bring it more fully into the 20th century.

Movie Magic Screenwriter 6.0 Serial Key Free

Neither site makes me feel like these two companies, ostensibly on the forefront of screenwriting software technology, have much clue as to what being a software company in the second decade of the 21st century is supposed to look and smell like. But then again, maybe they’re not targeting me, as I’m already a committed user of both. And no offense to either company’s web team.

The Bloat

Lastly, I’d be remiss if I didn’t rant for a spell on the amount of features in these two scriptwriting apps that I feel are worthy of leaving out of the next iteration.

Text-To-Speech

I’m not sure many screenwriters actually use this extremely clunky feature, where several terrible robot voices read your script to you out loud. The delivery, word emphasis, speed, tone, and character are wrong or laughably not helpful. I can understand Accessibility issues and that writers who may be physically disabled may rely on this, but the only thing it seems to do for me is add to each app’s bloat.

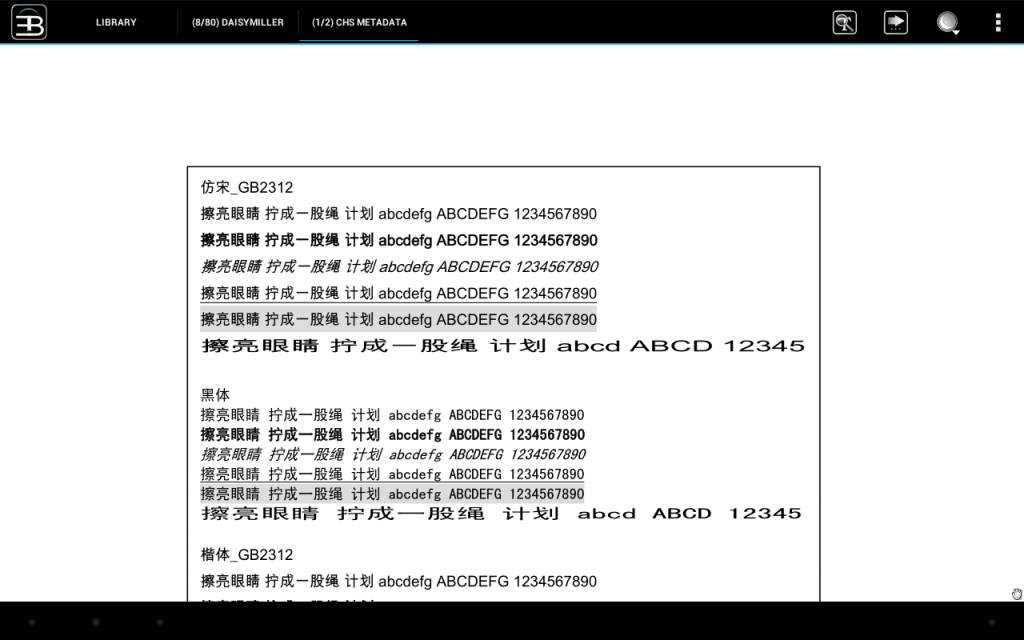

Fonts Could Use Some Rethinking

Both Final Draft and Screenwriter allow changing fonts granularly. That is, each element — scene heading, action text, character, dialogue, etc. — can have its own font and font size, if you want. In almost 30 years of screenwriting, I’ve changed the overall font of a screenplay many dozens of times — mostly from one Courier-based font to another for whatever reasons — but I’ve never had the need to make the scene heading one font and the action text a completely different one.

A simpler way to approach font would be to (a) limit the amount of fonts you can choose from to only the Courier-based fonts, (what screenplays ever use any other font than a Courier based font?), and (b) remove the ability to granularly control the font on a per-element basis. That is, remove all the complicated pull down nonsense and just give us a simple toggle that changes the font of the entire document.

And finally, put some time and thought into how the font looks and feels. I’m writing this article using an OS X app called Typed. The font I’m writing with is called Typed Pro. And as I type, the characters appear on the page as if I’m reading an old book — they’re beautiful, they’re easy on the eyes, and they just, flow.

Courier Final Draft and Courier New are fine, but Courier Prime from John August takes the cupcake when it comes a good looking, well-rendered Courier-based screenplay font. Why can’t it be the standard in Final Draft and Movie Magic Screenwriter?

Misc. Utilities

The “Names Database” in Final Draft, and the “Name Bank” in Movie Magic Screenwriter are kinda nice to have, but pretty unnecessary when I can just switch over to my browser and Google every possible name on the planet. What’s more, the Name Bank in Movie Magic Screenwriter seems to be disabled presently, in order for the program to work in OS X Lion (which originally shipped in 2012)

When it comes to comparing two documents, both FD and MMS have a feature to do that, and I can see some sort of need for this in a production environment, when scripts that aren’t locked, or aren’t locked correctly, or aren’t properly marked for revisions, etc., can make things pretty hairy from draft to draft.

But this feature, along with MMS’s ability to mark one character’s dialogue, and the “Statistics Report” in Final Draft — where you can do a tally of words, curse words, how much a character speaks, and a whole lot more — all of these and a slew of other features seem like they’d be better of all clumped into their own completely different section. For example, a “Utilities” section.

This would keep the writing interface as clean and as elegant as possible while giving all the technical, non-writing features that both suites do so well with, their own discreet section. Similar to the Developer menu in Apple Safari, where you have to enable the Developer mode in Preferences in order to even see the Developer menu item on the top menu.

Not interested in word count or breaking down the script for production? Only interested in a beautiful, clunk free writing experience? Then there’s no need to enable the Utilities menu item.

In Closing

The bottom line is that both of these apps are, yadda yadda powerful and full of features yadda yadda. And both of these apps are used by a lot of film industry professionals yadda yadda. But both suffer most when it comes to three key areas:

Price, Elegance, and Modernity

While the price point of FD and MMS leave a lot to be desired, I feel there’s hope. From where I sit, the price for either app can more readily be justified if both the elegance and the modernity of either program was raised by even just a little.

Slim down the bloat, or put all the stuff that most writers don’t need or want access to in their own separate tool or section or menu. Provide a more elegant writing environment, with a nicer font, and a cleaner interface — writers are suckers for the “smell of the typewriter.” It’s one of those few sensory things we romanticize and cling to, as people who are at the very heart of the creative process, yet so often working apart from the entire process.

And no offense, but get with the times, FD and MMS! The way forward is not proprietary script files. Make your money from the strength of your design and ideas and how easy you make it for screenwriters, not from the Bill Gates 1987 method of locking people into a proprietary workflow. You both became standards because of how good you are, yes, but you also owe a lot to your file formats. I don’t blame you though, you were pioneers in the field and that’s how it was done. But time marches on.

Let us open all script documents from all ages with your software. Let us convert all script formats to other script formats with your software. Let two or more of us be able to log in to Twitter, Gravatar, Tumblr, or even (ugh) Facebook, and then with a click open your software and work on the same exact page with each other, in real time, a la Writer Duet. Keep our dictionaries and custom dictionaries as fresh as an update from the atomic clock. And for God’s sake, give us an interface that works with the Oculus Rift VR headset.

Okay, I’m kidding about that last one. Although that actually might be pretty goddamn rad.

My choice between these two apps, although I use both, ultimately comes down to this:

I prefer writing in Final Draft, but when I’m ready for production, I find the tools in Screenwriter a lot easier and more familiar to work with.

But in all honesty, I’ve been giving a lot of finger time to the apps Fade In and Highland, primarily due to the simplicity and speed, real or imagined, that I experience when writing in either of those apps. Although Highland has thrown me a few hiccups and doesn’t quite measure up to Final Draft. But Fade In, as I use it more and more, is growing on me.

But if you’re entering the screenwriting software market and you feel you have to choose between Final Draft and Screenwriter, and none of the other promising new apps like Fade In ($49), and I have $200 or so burning a hole in my pocket, then I’d have to recommend Final Draft, by a mere Barton Fink nosehair.

If you have cleaned up your USB flash drive, FonePaw Data Recovery will works as a doctor to recover the lost files on removable storage media. You can recover the missing data caused by formatting the partition, re-partition, deleting the partition mistakenly, system crashing, improper cloning, etc. https://ertemusa.tistory.com/4.

If you’d like to be able to open and edit Final Draft files, and want a cleaner, leaner interface, and want to save about $200, buy Fade In. I’ve only started using it about a year ago, but it’s proving to be a solid alternative to the “Big Two.” Argh. There I go again.

Write Brothers Movie Magic Screenwriter 6 ($249 but on sale as of this post for $169) Revision 6.0.10.165 (R10)

Final Draft 9 ($249) 9.0.7 Build 184